Dubai is a Continuous Monument. The concept is envisioned by the radical architecture research of Superstudio. If you are unfamiliar with their practice, you can read about it here. This article draws a parallel between architecture critique of the 1960s and the current state of Dubai architecture and urban planning.

Introduction

Dubai is not a city that evolved progressively, over centuries, like European cities have. It is a city that more or less spawned itself as a modern metropolis built for scale, from the ground up. When discussing slow, steady and somewhat sustainable growth, we tend to use the word “organically.” However, one can argue that the “organic” nature of urban development is an exaggeration, if not even hypocritical.

Unlike historical cities that adapt architecture to both local heritage and contemporary needs, Dubai made a conscious decision to construct a new narrative altogether. A narrative driven by ambition, shaped by climate, and most importantly, determined by the free market.

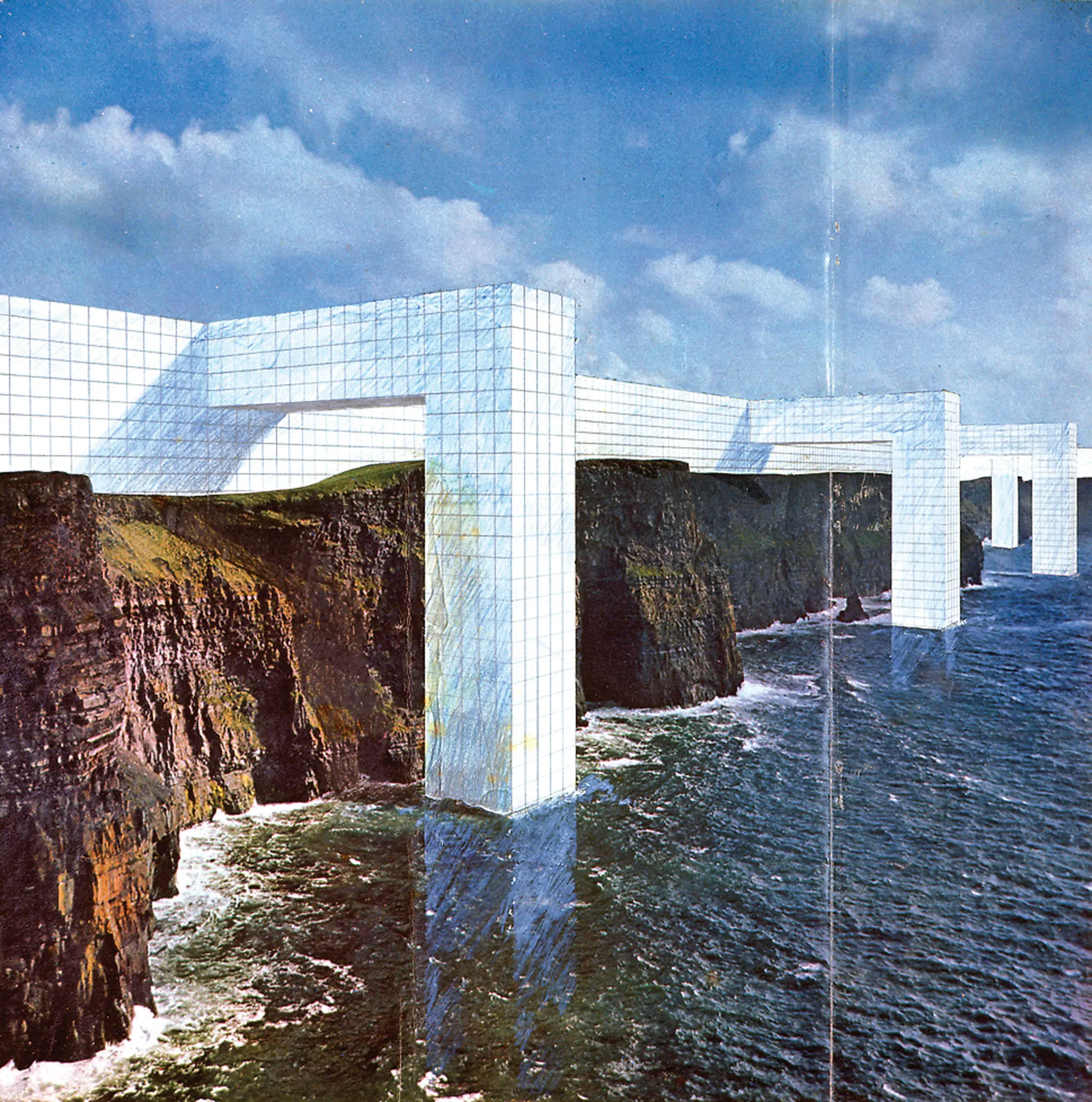

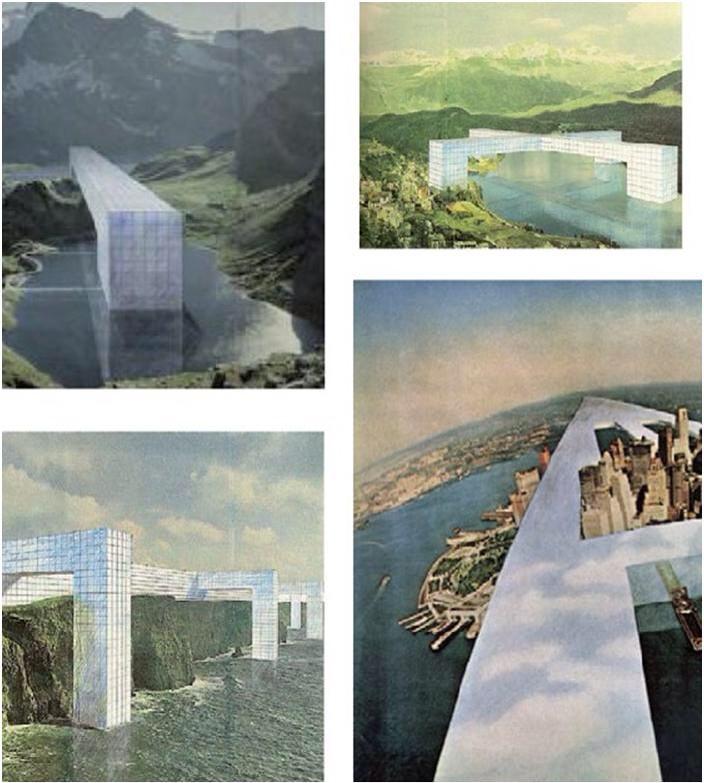

The iconic skyline of isolated towers. The vast, climate-controlled shopping centers that act as substitutes for public space. These two key traits of Dubai urban planning start sounding pretty familiar to someone who studies architecture. Dubai evokes two of the most radical architectural concepts ever imagined. Superstudio. They were a group of visionary Italian architects in the 1960s, used design research to put together a series of provocative ideas. Their projects were supposed to act as tools for architecture critique. They were never meant to be built. Yet, in many ways, Dubai has done exactly that.

Dubai Architecture is a Continuous Monument

In 1969, Superstudio envisioned the “Continuous Monument”. This was a seamless, gridded megastructure that spanned the entire globe, neutralizing the earth’s diversity beneath a single, rationalized system.

Dubai’s skyline is its own version of that monument. Towers repeat in clusters along Sheikh Zayed Road, soaring in height, homogenous in function. These towers rarely speak to one another. There is no shared language beyond ambition, no underlying “old city” to anchor them. Instead, each high-rise is a self-contained statement, connected more to economic forces than to urban tradition.

This is not accidental, but more of a consequence of the free market and minimal government intervention. It is the manifestation of a system that prizes scalability over adaptation. In Dubai, land use is negotiated more by spreadsheets than by urban planning regulation. In real estate there is no past. Design is dictated by ROI, density models, and free zone incentives.

A City Built for Scale

Dubai’s defining trait is not tradition but scale. It does not retrofit. The starting point is at 10X. From constructing artificial islands, building the world’s tallest tower, or planning entire neighborhoods on reclaimed land, to the colossal road infrastructure and ports that could fit ships larger than they even exist – the initial design is already scaled up.

If most European cities inherit architecture, Dubai builds for performance. The design logic follows capital efficiency and climatic necessity. There is no such thing as aesthetic nostalgia. European neoliberal cities rely on homogenous imagery to attract visitors, while Dubai is unapologetically high performance.

The Free Market as Urban Designer

Dubai architecture isn’t an arbitrary result. It’s the logical outcome of the effects of the free market, unleashed at an urban scale. Dubai’s growth has been governed not by a masterplan of urban hierarchy and juxtaposition of shared, public spaces. It is shaped by policy tools that attract foreign capital, labor, and enterprise. A few of these stand out:

- Economical free zones define urban planning asymmetrically more than historical aspects.

- Property law, together with zero property taxation, encourages experimentation and not preservation.

- Hospitality and retail sectors shape urban form. The commodified city is the result. It is both consumable and constantly refreshed.

Conclusion

The practice of Superstudio was meant to be satyrical, acting as a cautionary tale. Dubai, materializes these extremes. Of course, there was no dystopian intent. Unrestricted pragmatic ambition shapes Dubai architecture. This is a city that has turned ideological fiction into urban form. The drive came not from manifestos, as is the case with modern architecture, but by markets.

The city of Dubai is both:

- A Continuous Monument in vertical form. Economic units of measure dictate the cell size of the grid. It is both modular, rational as well as opulent, gleaming.

- A Supersurface in function. Highly controlled shared spaces distribute life, climate and commerce in layers of air-conditioned circulation.

Dubai, as well as its family of Emirates, reflects the country’s leadership’s intent to built for resilience. Historically, the obsolescence their economy had suffered when pearling no longer was sought was a multi-generational traumatic event. In order for the UAE’s economy to never have to go through this again, the fundamental rule of design is future-proofing through scale. Scale becomes the language of possibility.

Sources

Books on Superstudio and Radical Architecture

- Lang, Peter, and William Menking, eds. Superstudio: Life Without Objects. Milan: Skira, 2003.

- Galilee, Beatrice. Radical Architecture of the Future. London: Phaidon Press, 2021.

- Gausa, Manuel, et al. Utopie Radicali: Florence 1966–1976. Florence: Centro Pecci / Quodlibet, 2017. (Exhibition Catalogue)

- Colomina, Beatriz, ed. Clip, Stamp, Fold: The Radical Architecture of Little Magazines 196X–197X. Barcelona: Actar, 2010.

- Tafuri, Manfredo. Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development. Translated by Barbara Luigia La Penta. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1976.

Books on Dubai, Urbanism, Scale

- Ali, Syed. Dubai: Gilded Cage. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

- Krane, Jim. City of Gold: Dubai and the Dream of Capitalism. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2009.

- Graham, Stephen. Vertical: The City from Satellites to Bunkers. London: Verso, 2016.

- Koolhaas, Rem. Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan. New York: The Monacelli Press, 1994. (Free Download)