The Practice of Superstudio

Superstudio was a radical Italian architecture collective founded in Florence in 1966 by Adolfo Natalini and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, later joined by Roberto Magris, Gian Piero Frassinelli, Alessandro Poli, and Alessandro Magris. They were central figures in the Radical Architecture movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, which challenged the values, aesthetics, and purpose of modern architecture.

Core Concepts and Philosophy of Superstudio

Superstudio was less interested in building real architecture and more in critiquing the profession itself. They questioned the role of architects in capitalist society. They looked into how architecture shapes our lives. Their work was utopian, dystopian, and conceptual. They would use techniques such as collages, drawings, films, and photomontages as their main media instead of architectural floorplans and models.

Superstudio Key Themes

- Rejection of consumerism and formalism in architecture

- Critique of modernism’s failures to deliver meaningful change

- Exploration of architecture as a system of control

- Using irony, fiction and visual story telling as critical tools

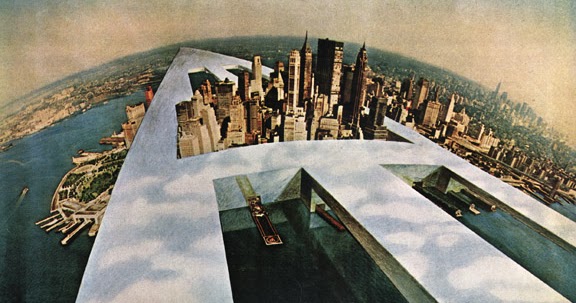

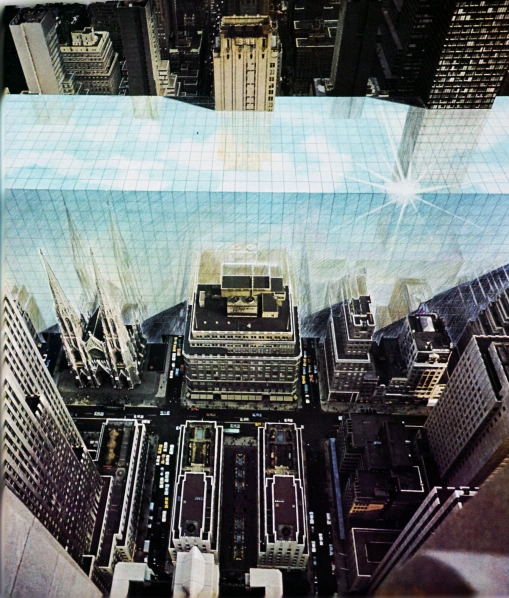

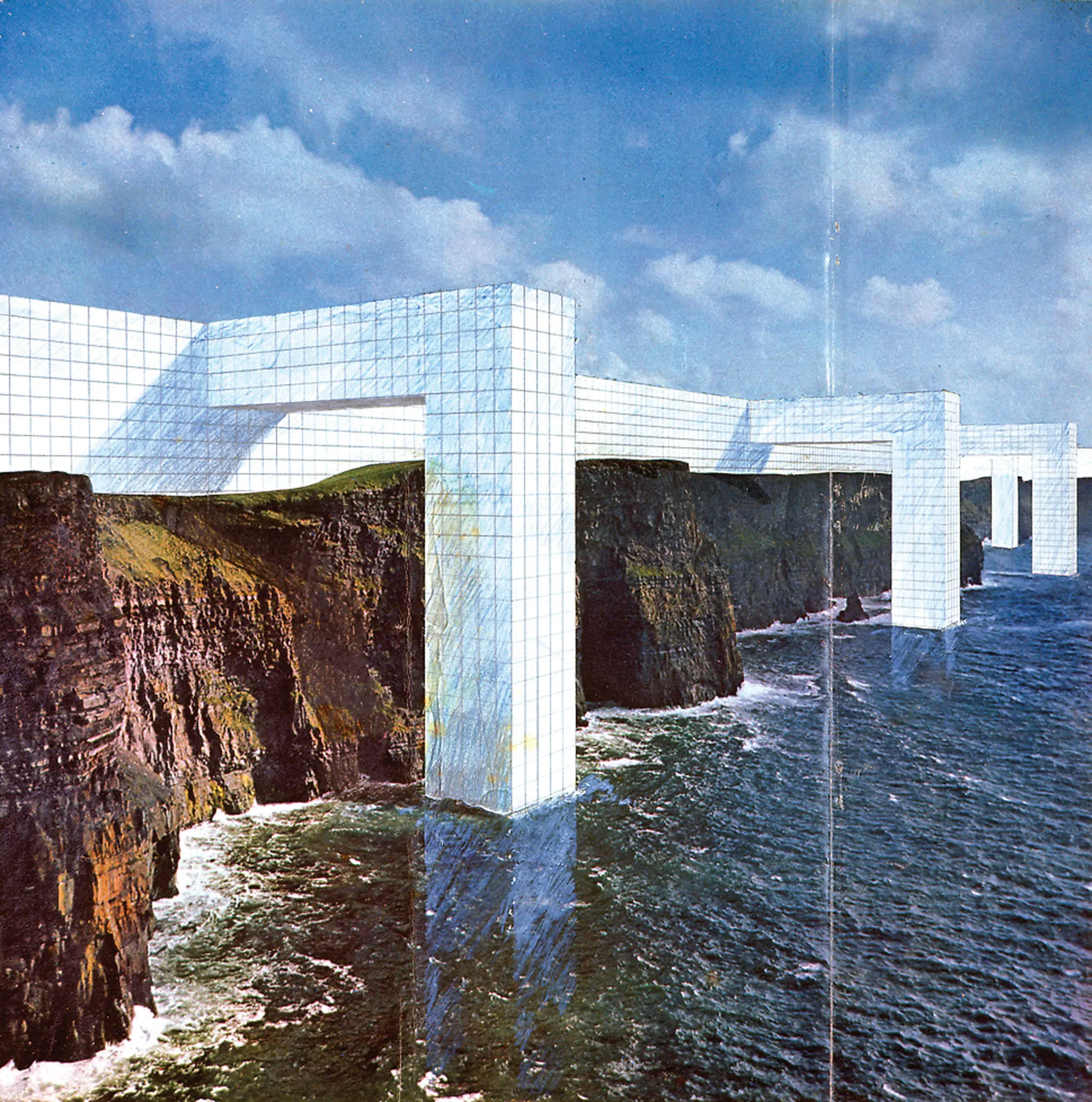

The Continuous Monument (1969)

The Continuous Monument is Superstudio’s most iconic conceptual project. It’s a global megastructure, a seamless grid-like architectural object that spans the Earth. It was never intended to be built, but to provoke.

Conceptual Meaning

1. The Endless Grid as a means of Total Order and Control

The Monument is a metaphor for the extreme rationalization of architecture. It embodies the modernist fantasy of total order but also becomes a critique of it. It shows the absurdity and alienation of such control.

2. Anti-Architecture as Architecture

The Monument erases all cultural, historical, and ecological context. It becomes a blank, universal infrastructure. It demonstrates what happens when architecture becomes pure system and loses meaning.

3. Critique of Urban Sprawl

It’s a commentary on the global spread of sameness and the lack of connection to place in modern urbanism.

4. A Hybrid between Utopia and Dystopia

The project is utopian in scale and ambition, but dystopian in feeling. Superstudio depicts it as monotonous, dehumanizing, even surreal.

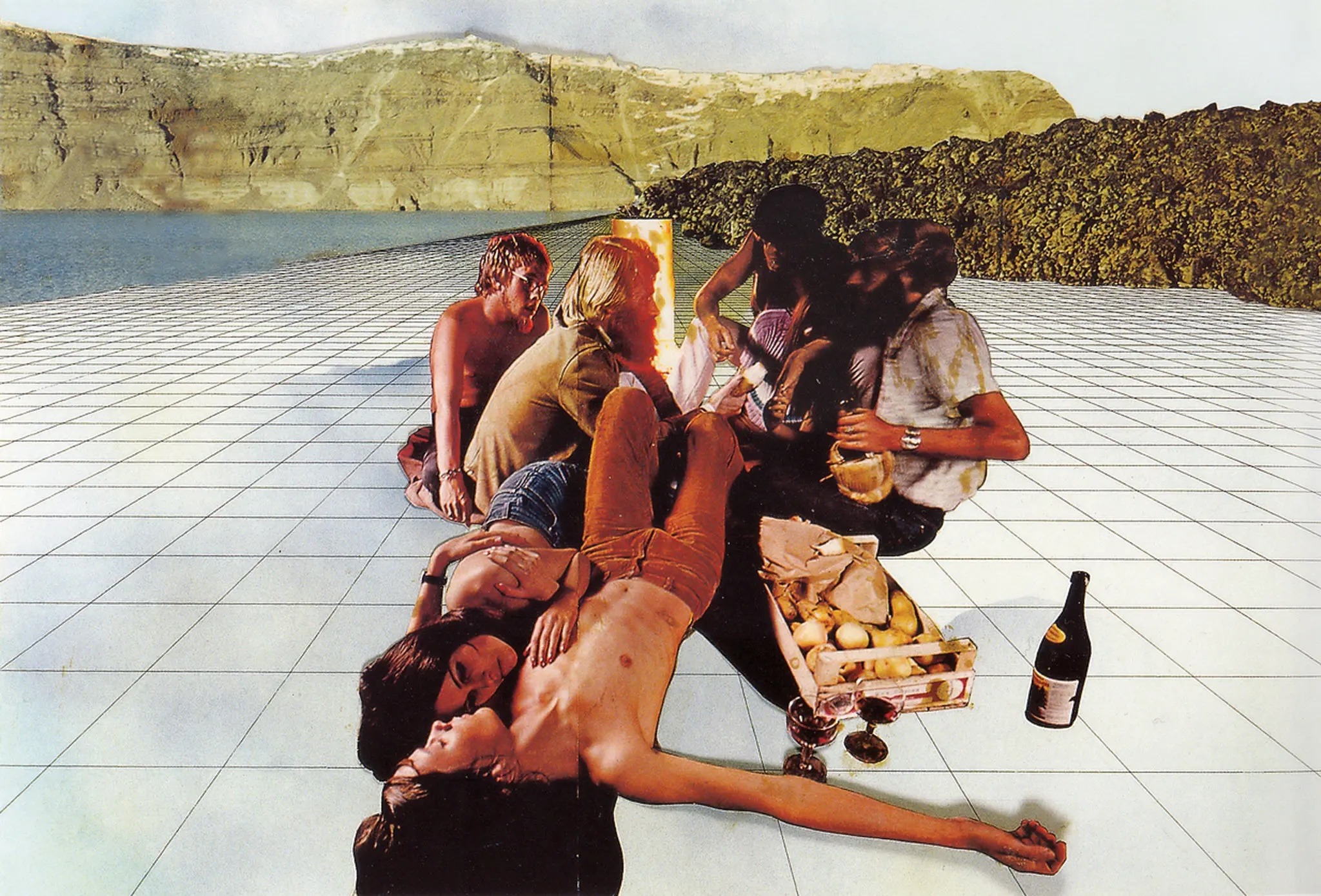

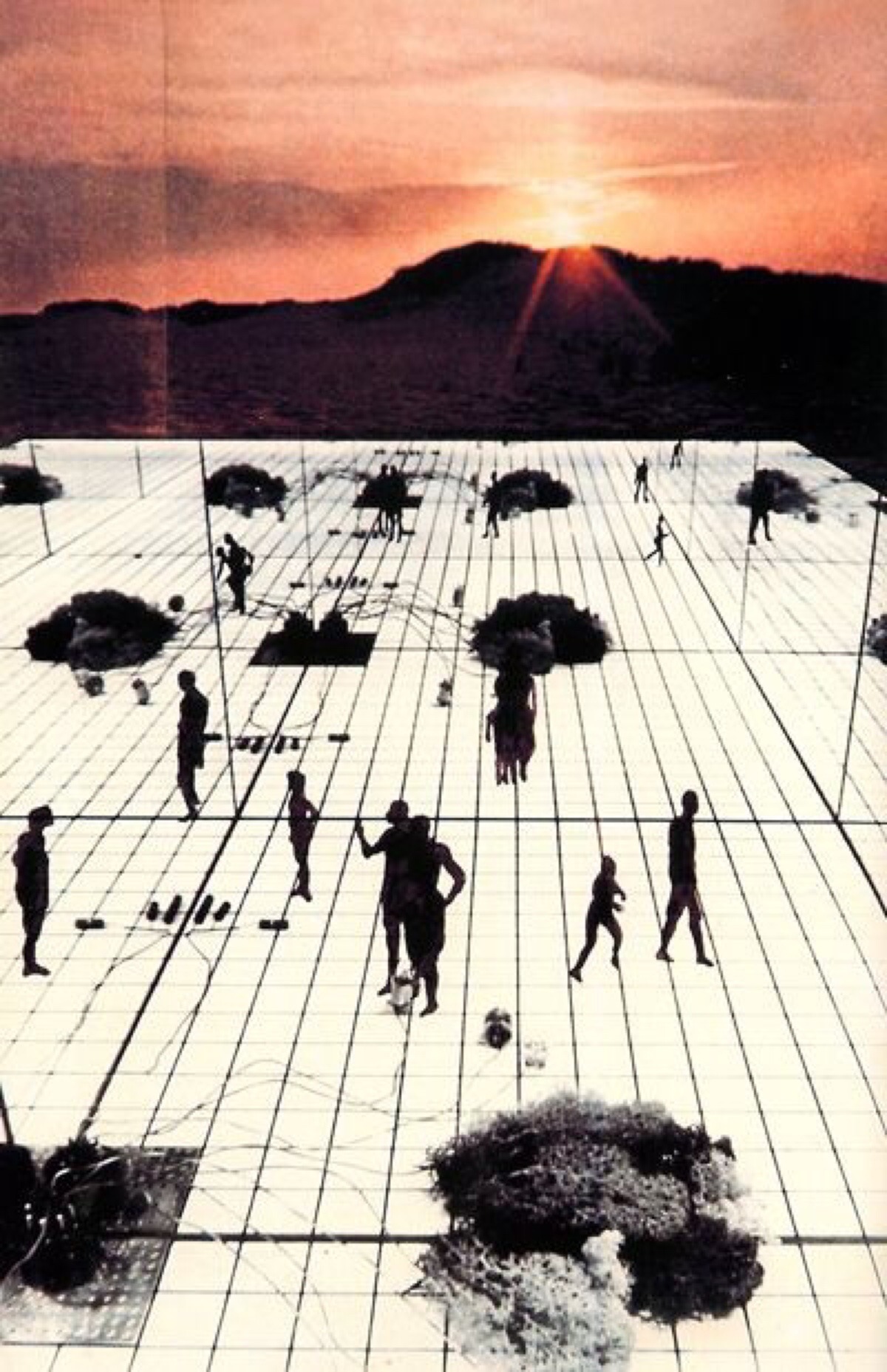

Supersurface (1972)

One of Superstudio’s most visionary projects, Supersurface reimagines the very foundation of how humans inhabit the world. Rather than building more, it proposes building less. Supersurface eliminates architecture altogether in favor of a universal technological grid that sustains life invisibly. It was presented through photomontages, storyboards, and film in MoMA’s groundbreaking 1972 exhibition “Italy: The New Domestic Landscape.”

Conceptual Meaning

1. Infrastructure without Architecture

Supersurface depicts a world where all the essential functions of life, energy, information, nourishment, are delivered invisibly through a global grid. There are no buildings, no walls, no cities. People live nomadically across a connected landscape, supported by a hidden technological substrate.

2. Freedom through Dematerialization

By removing architecture, Superstudio envisioned a radical kind of liberation. Humans are no longer constrained by property, labor, or design. The grid becomes a support system, not a symbol of control. It hosts an egalitarian way of living based on choice rather than need.

3. Critique of Design as Control

If the Continuous Monument showed the dangers of overbuilding, Supersurface warns of the illusion of progress offered by technological environments. Even utopias risk becoming systems of quiet oppression. The oppression comes from what lies beneath the surface: consumption, surveillance and social programming.

4. Alternative to Consumer Urbanism

The Supersurface is a response to the failures of modernist housing and capitalist urban planning. Instead of repeating typologies, it proposes a world with no typologies at all. What is left are only humans, nature and a seamless interface of invisible support.

5. Post-Architecture Utopia

Some would call the Supersurface anti-urban. I would argue it’s post-urban. It asks: What if architecture could vanish, and only life remained? Is that really such a bad thing?

Conclusion

In 2025, the idea of vanishing architecture can be seen as a consequence of the global network of information and interaction.

We witness the births of continuous monuments constantly in extreme climates. Soviet architecture had Brutalist urban planning, huge megastructures for housing. Steven Holl has the ground scraper, a building wedged inside the natural landscape. Moreover, The Middle East has urban super structures such as Saudi Arabia’s The Line and, most relevant, the architecture and urban planning of Dubai.

We also see a life sustaining supersurface that is the Internet. We can work from anywhere, we can order anything, including services, to wherever we chose to be. We can live off finances provided by the global market.

And yet, this level of freedom makes us seek out some forms of limitations, of conformity. That’s what the expensive cars are for. – read the Dubai article.